How Star Trek changed NASA, helped save the whales, and more

When Star Trek first aired in 1966, popular science fiction didn't take the science part too seriously. Alien abduction movies didn't get into the physics of how those tractor beams worked; biologists were rarely on hand to explain how, exactly, radiation exposure turned tiny insects into giant, hulking monsters. Star Trek has never exactly obsessed over realism either—but, long before being a geek was considered cool, the show was nakedly pro-science, casting scientific experts as heroic explorers who frequently use their technical know-how and superior reasoning to save the day. Teleporter technology and warp engines may be fanciful, but they show science's potential to bring about a better future. Star Trek isn't very scientific, but it is arguably science's biggest fictional cheerleader.

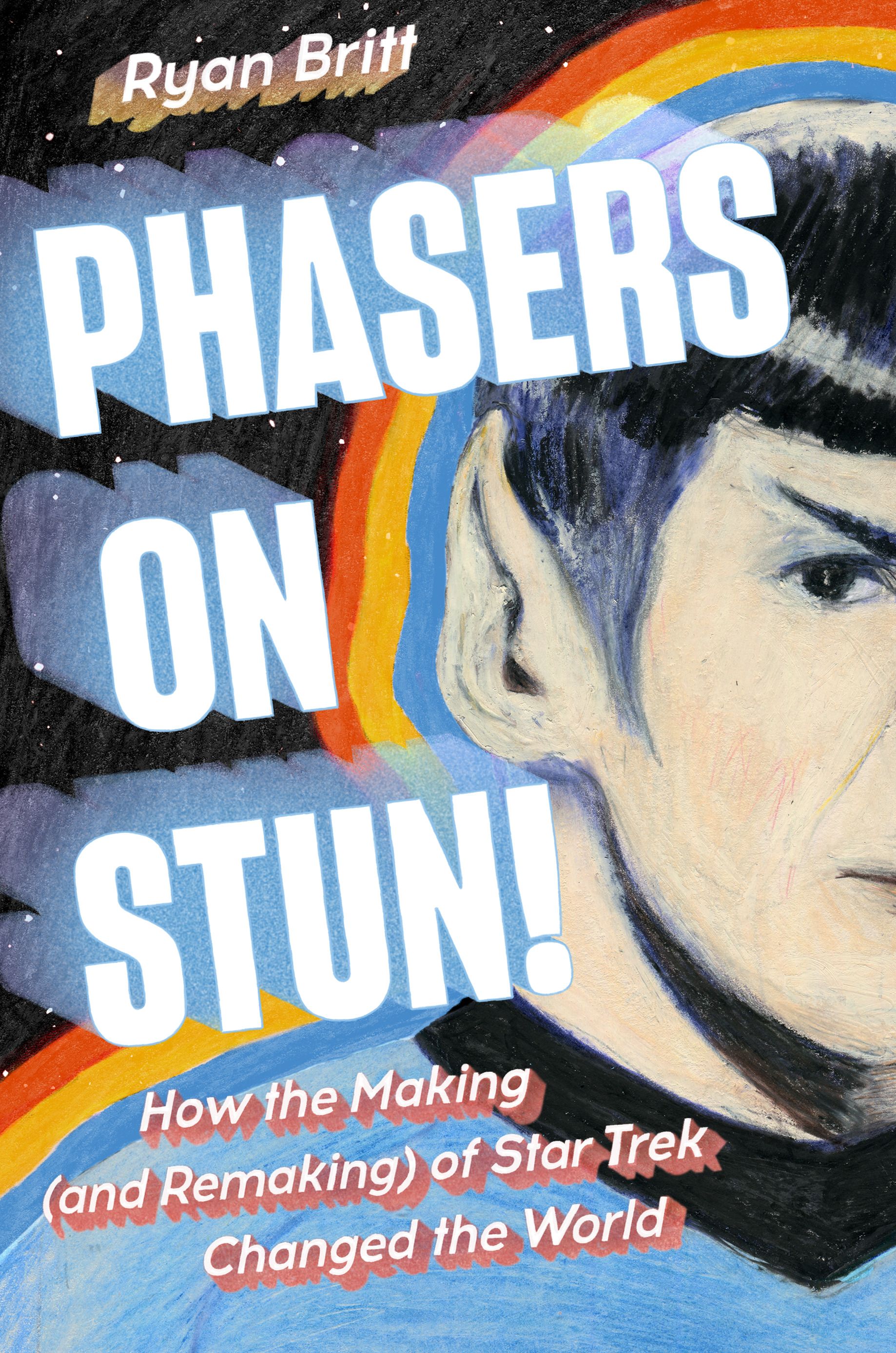

That helps explain why many so many Trek fans grew up to be scientists, why NASA named its first Space Shuttle Enterprise, and how actor Nichelle Nichols (Lieutenant Commander Uhura in Star Trek's Original Series) got a gig recruiting women and people of color to the space program. These are just a few of the fascinating intersections between science and Star Trek journalist Ryan Britt chronicles in his new book Phasers on Stun!, a deeply researched history of Star Trek and how it changed the world. From the inception of the Original Series to currently-airing shows like Strange New Worlds, Phasers on Stun! gives Trekkies of all generations a behind-the-scenes look at the making, and incessant remaking, of Star Trek through interviews with writers, actors, producers, fans, and more. If the book offers one simple takeaway about Trek, it's probably best summed up in the words of science fiction legend Octavia Butler: "The only lasting truth is Change."

That's as true for the franchise's relationship with science as it is for Spock's temperament or LGBTQ representation in Star Trek. The Science of Fiction spoke with Britt about the symbiosis between Star Trek and real-world science, the collision between NASA and Star Trek in the 1970s, and how Star Trek really did help save the whales. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How would you describe Star Trek’s relationship to science? I feel like on the whole, the franchise is very pro-science, but at the same time, I wouldn’t call Star Trek a hard science fiction show. This isn’t a franchise that tries to be physically realistic in terms of space travel. But it’s also not premised on the existence of mystical forces the way that Star Wars is.

I would say Star Trek’s relationship to real science is, for itself, somewhat mercenary. It just sort of takes what it needs. But it also is aspirational. It’s aspirational insofar as science, and knowing science, frequently saves the day, right? So you have that line in Discovery Season 2 where Ethan Peck [Spock] goes ‘I like science.’ Or Tilly and Stamets giving each other high fives and saying ‘This is the power of math, people!’ There’s a lot of that. And in The Next Generation that sorta came across through technobabble. But I think it was always gesturing at science.

A big part of the book, in chapter five, is the relationship that Jesco von Puttkamer has with the cast of the Original Series. He was this guy who worked at NASA and then advised Roddenberry on The Motion Picture, which is how we got the word ‘wormhole’ into an actual science fiction movie. And in theory, the wormhole that appears in The Motion Picture is probably Star Trek’s most scientifically accurate wormhole, because the idea is that it’s an Einstein-Rosen bridge that’s created on accident and it’s unstable. [Editor’s Note: Einstein-Rosen bridges are potential shortcuts through spacetime borne from Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Their existence in our universe has not been proven].

That was not something Star Trek has done subsequent to that. Wormholes are kind of whatever the show wants them to be.

I’ve interviewed Naren Shankar many times for The Expanse. [Editor’s Note: Naren Shankar was the showrunner for Amazon’s adaptation of The Expanse book series. Read The Science of Fiction’s interview with him here.] Naren was a science advisor on The Next Generation. And if you interview him now, he’s very flippant about it. He’s always like ‘we invented a fake science and we were the keepers of the fake science.’ Which, in The Next Generation, you can kind of see. Like ‘here’s how a tachyon beam works within Star Trek.’

Right. Or ‘here’s how the di-lithium crystals power the warp drive’. We’re told there’s some science behind it, but we don’t really get into the weeds about how it works.

Right. But then, you go back to the Original Series, and Roddenberry was running things by the RAND Corporation because he wanted the aerospace to be as realistic as possible. So, they didn’t use Chelsey Bonestell’s art directly [Editor’s Note: Bonestell was a 20th-century astronomical artist best known for his physically realistic paintings of Saturn and its moons], but they were trying to go more toward that than Buck Rogers. Roddenberry didn’t want flames coming out the back of the Enterprise.

So there was definitely an obsession with not doing certain things other science fiction properties did. But I would still say Star Trek is soft science fiction because it’s not like we get into the nitty-gritty that often. If you’ve got The Expanse over here and Star Wars and Guardians of the Galaxy over there then Star Trek is sort of in the middle, I suppose. And Doctor Who is just kinda popping around wherever it feels like.

I think that’s fair. Taking liberties with what’s physically plausible is in the DNA, but at the same time, there has always been a respect for science.

I think what’s more important [than the scientific accuracy] is the historical context. Before Star Trek, you never had a science fiction show in the mainstream that even cared a little bit. And then, when you get to The Motion Picture, Roddenberry has Puttkamer on the payroll, and they’re doing presentations— him, and Nichelle [Nichols], and Roddenberry—for NASA, together. That never happened before. And arguably doesn’t happen now. The closest would be NASA did some promotion with the new Lost in Space. But there’s a reason why a lot of people who are part of NASA are Star Trek fans.

To follow up on that, Chapter 5 of your book discusses the tie-ins between NASA and Star Trek. In particular, you focus on Nichelle Nichols, and the imprint she left on the space program when she started publicly taking the agency to task for having an all-white, all-male astronaut lineup. And this led to her teaming up with NASA to recruit women and people of color to become astronauts.

I'll confess, I was shamefully undereducated about this history. I knew a little bit about Nichelle’s involvement with NASA but I was amazed to read how deep it went. How significant was that for NASA, in terms of influencing the trajectory of the space program?

I mean, we were all completely undereducated on that. The person I have to really credit for bringing that to the mainstream is Todd Thompson, who directed the documentary Woman in Motion, which came out in 2020. I interviewed Todd about the documentary and a lot of that informed that chapter. But I went to some other sources, too, including Nichelle’s own memoir, in which she spends less than a chapter on that. Which is shocking!

So, the story basically is, 1976, the Space Shuttle Enterprise is rolled out and the Original Series cast, sans William Shatner, is present for the ceremony. And Nichelle, in her memoir, is like ‘cool, they named a space shuttle Enterprise.’ And most documentaries and books about Star Trek kind of stop there. Trekkies wrote some letters and Gerald Ford decided to change the name of a spaceship! Even though it didn’t fly in space.

But then Nichelle was like, ‘well, this is bogus, this is not the Star Trek future I’m seeing when I’m doing convention appearances with Jesco von Puttkamer and doing promotion for JPL and NASA.’ And so, because the Space Shuttle program was happening, and Nichelle Nichols had already formed a nonprofit group called Women in Motion which was about giving women opportunities they wouldn’t otherwise have, she decided to put her money where her mouth was and say ‘NASA, I will help you recruit women and people of color to the space program because I don’t believe they’re being reached.’ And she was right! Ron McNair and Sally Ride—these people wouldn’t exist in the Space Shuttle program without her. [Editor’s Note: Ron McNair was one of the first African American astronauts to fly in space, while Sally Ride was the first American woman in space.]

Nichelle Nichols also threatened to sue. She said to NASA ‘after if I do this if I still see a really white astronaut corps, I’m gonna file a class action lawsuit.’ So that’s interesting too, this idea of a celebrity who wielded power within a certain community who was also a person of color was saying ‘I will destroy you if this doesn’t work out.’

Like many, my all-time favorite Trek film is The Voyage Home. Not just because it’s an incredibly fun and funny movie and Leonard Nimoy was a great director, but because it’s really one of the best environmentally-themed pop culture successes of all time. Could you talk a little about how Nimoy’s concerns over conservation and the environment shaped the film, and also how the film itself impacted the public?

To answer the second part of the question first, people who worked at Greenpeace at the time noted an uptick of donations from ‘86 to 87, when the film would have been in its theatrical run. You don’t hear about that very often with other blockbusters. It’s not like The Force Awakens comes out in 2015 and people donated more to Amnesty International. It doesn’t happen.

Something that Nimoy said and is in the book is he didn’t want the fourth film to be about the Enterprise crew fighting bad guys. So I think the first thing about the film that’s really important is it’s a movie that has a giant conflict, but it’s not a conflict centered on us-versus-them. And I think that’s the opposite of something that would consider itself an environmental movie like Avatar, which is super heavy-handed, there’s clear sort of mustache-twirling, evil corporate types. What makes The Voyage Home so smart is all of that kind of happened off-screen in our present—we made the whales go extinct, and Kirk and Spock are just kind of confused. I think that point of view was really important for Star Trek.

So Nimoy was interested in having a film that had something to say and yet wasn’t about violence. But then, the thing about the Klingon ship flying in and getting in front of the harpoon? That was something Nimoy took from Greenpeace.

That was directly inspired by anti-whaling activists’ tactics.

Right. And to have it be Kirk, who’s somewhat conservative—to have Kirk, in their stolen ship, be like ‘we’re going to save these whales,’ I think that that communicated a lot. My family growing up was very conservative and they loved that film. And I think that’s really the power of it. It made environmentalism seem like a non-political issue.

While Star Trek generally presents a pretty pro-science worldview, the franchise also has a long history of warning us about how scientific advances can be abused and the dangers of certain types of scientific or technological progress. The two obvious examples I came up with were World War 3, the nuclear war in the mid-21st century that virtually destroys human civilization, which of course wouldn’t have happened without the invention and proliferation of nuclear weapons. And then, the Eugenics Wars, which come about as a result of attempts to genetically modify humans. How much do you think the theme of science run amok, or the dangers of science when it’s divorced from a morality code, is part of Star Trek’s DNA?

I think that tension is sort of what defines Star Trek sometimes. The show can’t come out and be like ‘technology is bad.’ That would make no sense because then they wouldn’t be able to do all the wonderful things they can do. They wouldn’t have warp drive, they wouldn't have all the wonderful medical advances they have, they wouldn’t be able to beam people. Star Trek is always aware that ‘we’re pro-science, we’ve gotta be careful.’ But I think there’s been an interesting meditation on it both in Picard and in Discovery.

Discovery Season 2 presented a rogue AI called Control that was bent on destroying and killing everybody. But then we also had the emergent AI on the Discovery which was protecting the crew.

If you look at Season 2 of Picard, it’s eventually a critique of how The Next Generation depicted tech paranoia, vis-a-vis the Borg. The Borg are sort of this anxiety that’s not fully realized: That your opinions, and your identity, could be sort of taken over because society values technology more than anything else. But what’s funny about that within The Next Generation is The Next Generation also is pro-technology. So the show is saying ‘we use technology in a different way, and we can stop ourselves, and the Borg can’t.’

I think it’s very telling that in the first season of Picard, you have Jurati, the roboticist, pick up a copy of Isaac Asimov’s The Complete Robot. Now, Issac Asimov’s robot stories end with AI protecting people, not taking them over. So then Jurati, at the end of Season 2 of Picard—spoiler alert—becomes the Borg Queen of the benevolent version of the Borg. Which is such an Asimov ending. It’s like, okay, technology is fine as long as the programmer is ethical. And Jurati’s character is this big fan of Data, and Data of course is this ethical robot.

Is there a particular Star Trek technology you are optimistic we will see within our lifetimes?

[Laughs.] You’re the science expert! I don’t know, I guess the universal translator? It feels like it’s the one closest? I see my wife and my daughter doing Duolingo, and I can translate stuff on my computer now, instantly, that I couldn’t ten years ago. That feels like Hoshi’s early tech from Enterprise coming true.