The real science behind Star Trek: Lower Decks 'quantum reality drive'

The reality-bending two-part series finale of Star Trek: Lower Decks was a joyous, exhilarating, and surprisingly science-heavy romp through the multiverse. Building off an idea from Star Trek: The Next Generation—that the Federation fans know and love is but one of an endless number of possible permutations—"Fissure Quest" and "The New Next Generation" reveal a rich tapestry of alternate realities where characters live and die differently, rank up or remain ensigns, and in some cases, exist only as holograms.

In addition to firmly canonizing the idea that Star Trek is set in a quantum multiverse, we learn there is at least one alternate reality where Starfleet's mission is to explore alternate dimensions, using a warp drive cousin called the quantum reality drive. And just as there's a real scientific foundation for warp drive, the quantum reality drive was inspired by actual concepts from the realms of particle physics, quantum mechanics, and cosmology.

"We think of our universe as a sheet of space-time that we live within," astrophysicist Erin MacDonald told The Science of Fiction. "The multiverse drive would allow you to basically pop out of that sheet."

MacDonald received her PhD studying gravitational waves. She now serves as science advisor for the entire Star Trek franchise, a multidimensional job that involves workshopping scientific storylines with the writers, reviewing technobabble-laden scripts for accuracy, and ret-conning Trek-universe inventions like di-lithium and subspace to give them a physical explanation. When the Lower Decks writers decided they wanted the series finale to be about the crew of the USS Cerritos confronting a threat to the entire multiverse, they brought MacDonald in early to discuss different ideas about how multiverses might work.

MacDonald, who has advised on every episode of every series since December 2019, said it was "one of the best relationships" she'd had with the writers' rooms.

"When it works well, it works great," MacDonald told The Science of Fiction. "I think this is a perfect example."

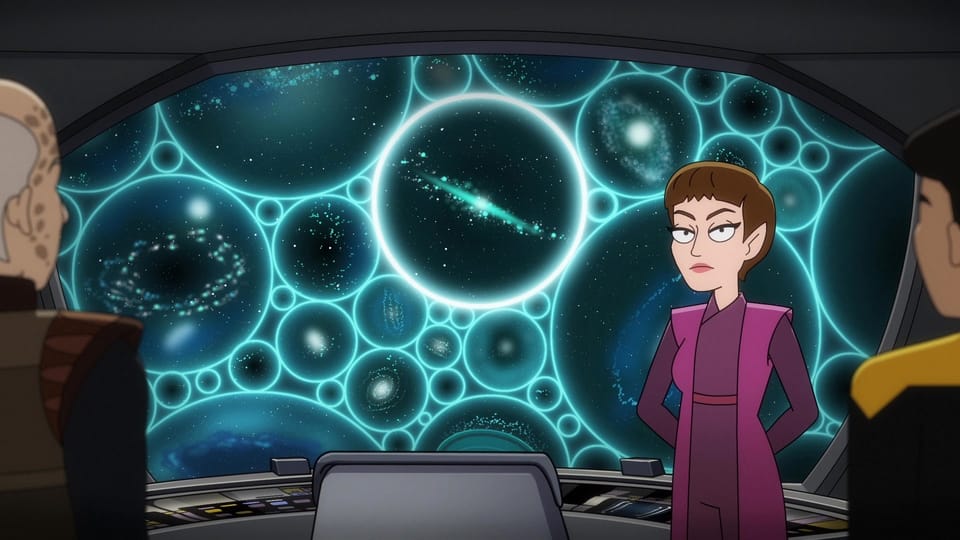

In "Fissure Quest," an alternate-reality version of Lily Sloane (who helped Zefram Cochrane develop warp drive in Star Trek's prime universe) captains the USS Beagle, a ship sent forth by its Federation to explore the multiverse. It does so by using a tachyon beam to tear open rifts in the fabric of reality. Then, the ship spools up the quantum drive's "unobserved complex gluon cores," whose lavishly nerdy name pays homage to Schrödinger's cat, a thought experiment about how particles are in a state of flux while they remain unobserved, as well as a real subatomic particle, the gluon, and some invented Trek science (more on that momentarily). The drive allows the ship to create a fifth-dimensional bubble, which it uses to pop out of its universe and enter a different one.

That is pretty much all we are shown about how the drive works, which leaves a lot to the imagination. But the script, MacDonald says, offers a few additional clues.

For one, the drive's name tells us that we are dealing with a quantum multiverse—one of several possible flavors of multiverse physicists and philosophers have proposed. The animating idea behind the quantum multiverse is that there are an infinite number of universes corresponding to all possible solutions to the quantum wave function. In lay-friendly terms, for every choice you make, there are other branches of reality where you make a different choice.

"It's this idea that small changes result in different universes," MacDonald said. " You might have a very similar life, but one or two things might be totally different."

MacDonald said the writers decided to embrace this vision of the multiverse—as opposed to, say, a cyclic multiverse where new realities are born every time a universe dies—because the Next Generation episode "Parallels" previously introduced the concept to the Star Trek canon. In "Parallels", Worf accidentally pilots a shuttle into a quantum fissure—a crack between realities—and enters a state of dimensional flux, randomly jumping between different universes.

"They took the idea of the Parallels episode, and they ran with it," MacDonald said, adding that it's common for the new shows to "layer more and more science" to support, and elaborate on, what earlier Trek series established.

But Worf didn't hopscotch across the multiverse intentionally, so how exactly does the USS Beagle manage it? Here, the writers had to get inventive. First, they decided, Sloane's ship would use a tachyon beam to tear a hole in spacetime—something we have seen the fictional faster-than-light particles do before to open transwarp conduits for the Borg.

Then there's the jumping itself. According to MacDonald, the idea for a drive fueled by "unobserved complex gluon cores" builds off science she invented to explain "The Burn," a cataclysmic event in Season 3 of Star Trek: Discovery in which most of the galaxy's di-lithium is rendered inert. Because di-lithium regulates the matter-antimatter reactions within a ship's warp engines, this has the unfortunate side effect of causing every active warp drive in the galaxy to explode.

While working on Discovery, MacDonald decided that di-lithium—a fictional Trek universe substance dating back to Star Trek's original series—is composed of both traditional atoms and subatomic particles as well as "complex" subatomic particles that exist outside of our spacetime plane, in the realm frequently referred to as "subspace." (In mathematical terms, subspace can be thought of as the imaginary plane, MacDonald says.) This gives di-lithium special properties, including the ability to contain the incredibly energetic reactions inside a warp core so they can be harnessed to create a bubble of spacetime around a ship. That bubble of spacetime then carries the ship at faster-than-light speeds.

Similarly, the "complex gluons" at the heart of the quantum reality drive exist in a hyperdimensional space, allowing them to bend the laws of physics. In this case, rather than enabling the formation of a warp bubble, the special subatomic particles catalyze the creation of an extra-dimensional field a ship can use to cross the barrier between realities.

"And that's pretty much the level that we got into engineering the science of it," MacDonald said.

After the Beagle enters a new reality, it uses a "gluonic beam" to seal the rift, thus preventing long-term damage to the fabric of the multiverse. Or... so Sloane and her crew think. What they don't realize is that every time their ship creates a rift, a second rift opens somewhere else to allow matter from the other universe to leak in. This prevents the ship's jumps from violating another fundamental law of physics: conservation of energy, which states that energy cannot be created or destroyed. Unbeknownst to Sloane and her crew, the rifts their ship leaves in its wake are weakening the integrity of the entire multiverse.

The nod to conservation of energy, MacDonald says, is a bit of an easter egg for the physics nerds.

"The reason a lot of multiverse theories fall apart is conservation of energy," she said, adding that it's hard to square the idea of a finite amount of energy in the universe with the notion that every choice spawns an entirely new one. "We really tried to work that in."

So, while Sloane's ship might be accidentally unraveling reality as we know it, at least it isn't doing so in a thermodynamically impossible way. But MacDonald emphasizes that there's a lot in Lower Decks' series send-off that doesn't hold up to scientific scrutiny—and in the entertainment world, that's ok.

"Any little science reference is just a fun, happy science reference," MacDonald said. It's "sprinkles on top."